“I am colonized, and I must live in a world of the colonizer. Although the proverbial shackle has been removed, I am enslaved by systemic barriers. My heart bleeds of pain and anger … My lived experiences will never be based on your level of comfort.”

– passage from the author’s journal

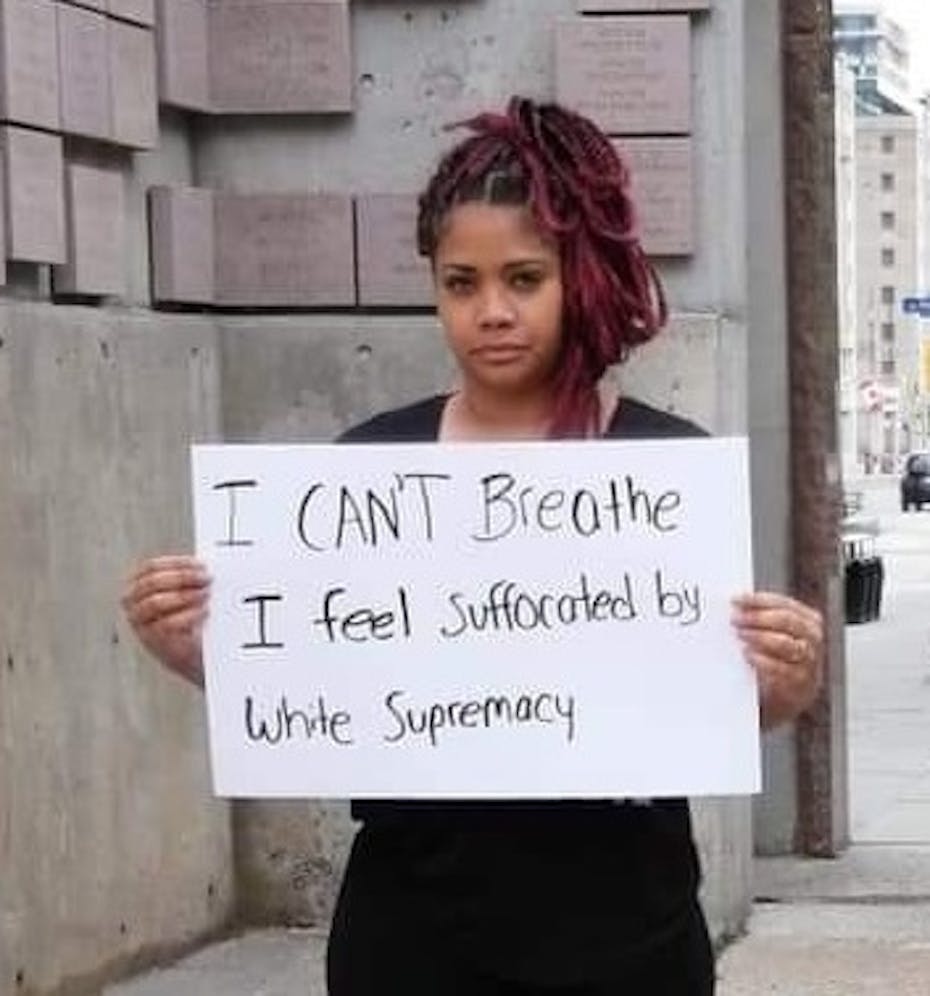

The recent resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement has ignited an ongoing debate on the role of education in the collective awakening or re-awakening on racial injustice.

Post-secondary institutions can provide the space to cultivate new knowledge and critically discuss social inequality. As the new school year begins, many of us are eager to return to our new “normal” as we both adapt to new health measures due to COVID-19 and prepare to discuss various social issues.

Universities are increasingly establishing formal mandates for addressing anti-Black racism on their campuses. In the attempt to acknowledge their diverse student bodies, some professors may be preparing to teach a new “inclusive” syllabus.

As these changes take place, it is critical to speak openly about social accountability.

Understanding one’s historical social position

I am a Black PhD candidate in sociology who examines systematic racism embedded in educational institutions.

I have found myself both formally and informally called upon to educate white people about anti-Black racism.

On many campuses, Black academics — regardless of whether they are actually studying racism or not — are asked to take on additional labour related to equity work often without compensation or the assurance that recommendations will be heeded and without acknowledgement of the risks.

What are the risks? Black, racialized and Indigenous people are exposed to white denialism, which provokes a narrative of “us versus them.” We are also subject to emotional eruptions where white people are at the centre or put in a position where they are pressed to offer personal antidotes as a testimony to the realities of systemic racism.

Interconnection of race, power, practices

It is critical that we pay attention to and recognize what scholars like George J. Sefa Dei, a professor of education, has named the interconnection of race, social powers and cultural practices.

White accountability for addressing and eradicating anti-Black racism isn’t about validating the experiences of the Black communities — it is about understanding facets of one’s own social position.

This means understanding the various ways that race or citizenship have shaped access to both material and cultural resources — and shaped what a person takes for granted. For example, white settlers in Canada and other colonial settler societies must acknowledge the harms associated with international colonization and the slave trade and the inter-generational effects on Black, racialized and Indigenous communities.

In order to undo anti-Black racism and all systematic racism white people need to take accountability for the various ways they experience and exercise privilege. It also means understanding how they may covertly benefit and contribute to the cycle of racism.

Sefa Dei has advocated for incorporating Africentric curricula and insights into everyday learning to undo the centring of white perspectives. But a deep incorporation of this knowledge hasn’t happened in universities.

Beyond ‘calling out’ & ‘calling in’

Executive coach Mya Hu-Chan, who helps workplaces address racism, notes that dialogues about addressing racism often revolve around being called out or called in.

This is a start, but much more needs to be done to create space for accountability if campuses are truly to become more diverse and inclusive.

We all have a social responsibility. The notion of community engagement and dismantling institutional racism involves everyone.

White accountability for addressing and eradicating anti-Black racism means understanding and acknowledging that verbal commitments must be also transformed into actions. The actions must be formed, validated and determined in dialogue with the Black community.

What accountability means

Accountability requires ongoing dialogue between the privileged and the underprivileged, and challenging the ingrained covert forms of racism embedded in our everyday lives.

Accountability also refers to entering a space with sincere purposes. But sincerity alone isn’t enough. Uniting your intent with action will ultimately determine a person’s level of commitment to anti-racism. By first understanding and recognizing our contribution to the systematic barriers, we shift the conversation from intentions to accountability.

Only when honest, open collaboration takes place can we begin to overcome the ingrained racist structures that shape all our lives.

Steps to create space for accountability

Based on my experience and research in the field of educating people about anti-Black racism I propose that creating the space for accountability requires the following:

Listening, trusting and empathizing with the lived experiences of Blacks or maginalized groups; NOT reacting. It is important that before white people engage in anti-racism spaces with maginalized people, they

manage their own defensiveness and become adept at regulating their emotions, including anger. They also need to to be aware of the intrusion of “saviour mentality” — the view that white people are especially equipped for and tasked with solving problems.Awareness and reflecting on your own social positioning: This means spending time in personal self-reflection and also in community contexts. In seeking to address and eradicate anti-Black racism, white people should seek to talk with other white people seeking to be committed to undoing anti-racism — but also with Black people in diverse spaces that are dedicated to anti-racism work.

Educating other whites about privilege and accountability. Calling out racist behaviour and white saviourism with resolve and humility in acknowledging that you too have had help in unlearning racist behaviours.

Developing an action plan that is facilitated and guided by the Black community.

Objective of equality

As Malcolm X states: “Education is our passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to the people who prepare for it today.”

But education needs to happen ethically in a way that respects Black people’s identities and experiences or else we are going the wrong way.![]()

Karine Coen-Sanchez, PhD candidate, Sociological and Anthropological Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.