When we decided last summer to create an undergraduate course about pandemics, we faced skepticism. Weren’t students and instructors tired of the COVID-19 pandemic? And would looking at pandemics from the perspective of numerous disciplines make it hard to address the topic with depth, or would we achieve a sense of cohesion?

As an anthropologist, a biologist and a historian, we know that infectious diseases are about a lot more than biology and medicine. Historically, epidemics and pandemics have shaped the world around us, from mask-wearing habits during plague times to the impact of polio on the Toronto school system of the 1950s.

And, just like COVID-19 has affected people differently depending on where they live and work or what social supports they have, so have epidemics of the past. The tragedy of our long-term care system isn’t new and understanding how infectious diseases might emerge and spread — and therefore how to contain them — is a complex matter involving everything from the science of contagion and human behaviour to social systems and the social determinants of health.

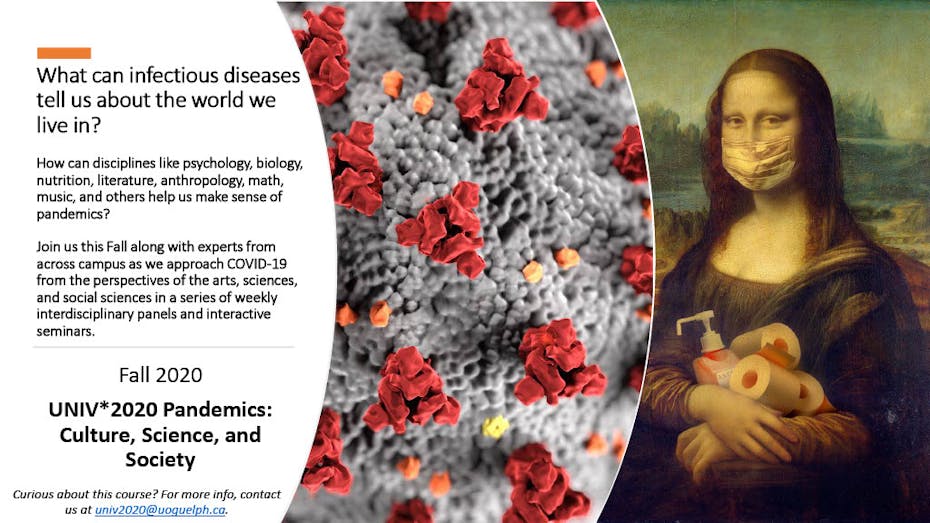

At the University of Guelph, we created “Pandemics: Culture, Science and Society.” This multidisciplinary course was offered in a virtual format and open to students as an elective in all programs and to alumni as a complete series of twelve weekly panels per semester.

We initially intended for this to be offered in fall 2020 only, but we quickly realized the value of our approach. We decided to run the course again in winter 2021, with a focus on COVID-19 research and creative projects that emerged at our university, from the sciences and the social sciences to business and the arts. Over two semesters, we engaged with 80 experts and researchers, as well as 600 undergraduates and 300 alumni.

From disease modelling to pandemics in art

Themes for weekly panels included knowledge and misinformation; pandemics in history and the arts; animals, environments and pandemics; and community, agency and resilience. Students and alumni learned about disease modelling, the impacts of COVID-19 on our food systems, pandemics in the ancient world and the biology of infectious diseases. Each week, panellists — faculty, post-doctoral fellows and other experts — gave short presentations, followed by moderated discussion.

We convened expert panels from departments of population medicine, integrative biology, geography and computer science to economics, sociology and anthropology, fine arts and music, history and others, engaging multiple disciplines at a time.

Panelists helped students and alumni sift through and make sense of the COVID-19 “infodemic.” Public health and media experts, mathematicians, biologists, psychologists and philosophers were able to answer questions on the usefulness of masks, suggest ways for students to navigate stressful disagreements with roommates or relatives about COVID-19, and help the class understand how testing models and vaccines were developed. Every week added another layer to class discussions.

Personal and virtual connections

As course organizers, we were learners too. Through class discussions, we learned how COVID-19 was affecting all of us — students, alumni and panellists — as many shared some of their experiences. The course demonstrated the ways in which academic knowledge and personal experience can relate and interact with each other.

We know that people experience and explain epidemics and pandemics in ways that are shaped by existing economic, political, technological and social circumstances and tensions. As anthropologist Lisa J. Hardy explains, to “understand social and political responses to the global pandemic, it is essential that we continue to investigate xenophobia, inequality and racism alongside the biological impact” because the effects of pandemics are unequal and shaped by societal divisions. This became one of the main themes of the course.

The course allowed us to explore our shared and individual experiences in living through COVID-19. Participants heard how different the experience of the pandemic has been based on factors such as sex and gender, socio-economic status, race and ethnicity, geographic location (for instance, rural versus urban), political circumstance, mental and physical health status and many other factors.

We learned about the resilience of the Canadian food system from farm to plate, as well as the ongoing challenges such as the reliance on migrant workers and bottlenecks in distribution. We gained insights into the experiences of

grocery store workers, persons with disabilities, pets and their people and musicians.

We benefited from expert discussions about the emergence and evolution of viruses, vaccine development and deployment, wastewater testing and many other technical topics. And, we witnessed the incredible creativity on display during a global crisis from colleagues across campus.

Course and a community

We also saw the potential benefits of virtual classrooms. The course and its weekly panels in a virtual format offered a model for linking students, alumni from all over Canada and the world, and researchers in an intellectual and supportive community. We believe the meaningful connections that were created would have been harder to develop in a large auditorium.

Even as the pandemic kept us apart physically, the course created a deeply engaging virtual community; some students and alumni told us the panels became a weekly high point for them, and alumni attendance and participation made it clear how much alumni value opportunities for lifelong learning that emerge from ongoing university engagement.

If the course felt for some like a community, it was in part because we were engaged in understanding the multifaceted dimensions and impacts of phenomena we were living through in different ways. So while this pandemic will pass, this course serves as a model for addressing complex and urgent challenges such as climate change, social and racial injustice, and global food and economic security.

Recordings of our fall 2020 panels are free to access here.![]()

Elizabeth Finnis, Associate Professor, Sociology and Anthropology, University of Guelph; Sofie Lachapelle, Professor, History, University of Guelph, and T. Ryan Gregory, Professor and Department Chair, Department of Integrative Biology, University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.