The impacts of COVID-19 on Australian university researchers are likely to have consequences for research productivity and quality for many years to come.

According to an online survey of academics at the University of Canberra between November 2020 and February 2021, they have deep concerns about their ability to undertake research during the pandemic and the flow-on effects of this. The findings are consistent with those of Research Australia from research in 2020 and 2021 and suggest Australia’s research sector will take a substantive hit from COVID-19.

The knowledge produced by university research generates an estimated 10% of Australia’s GDP. Without access to JobKeeper in 2020, universities across the sector cut back on casual staff and increased the teaching load of full-time academics. Combined with the challenges of working from home, this has had a real impact on research, not just immediately but in the longer term.

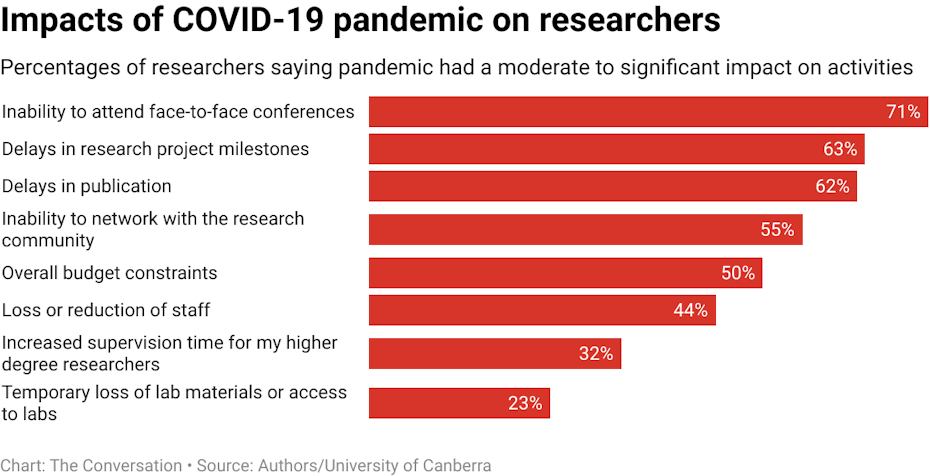

Almost three-quarters (73%) of respondents reported teaching commitments increased in the transition to online learning. Almost two-thirds reported delays in project milestones (63%) and publication (62%).

In addition to reduced research productivity, staff expressed concerns about the quality of outputs as they are aware their general mental well-being has been affected. As one academic said:

“Although I have completed the usual number of papers, I am concerned about their quality due to the sense of being so overwhelmed by work and the COVID impacts that I couldn’t apply my usual critical judgements.”

Impacts on researchers are highly uneven

About half (52%) of respondents felt positive about the flexibility of working from home. In fact, we may see a shift in the work culture following the pandemic. An Australian Bureau of Statistics survey in June found one-third (33%) of Australians said working from home was the aspect of COVID life they would most like to continue.

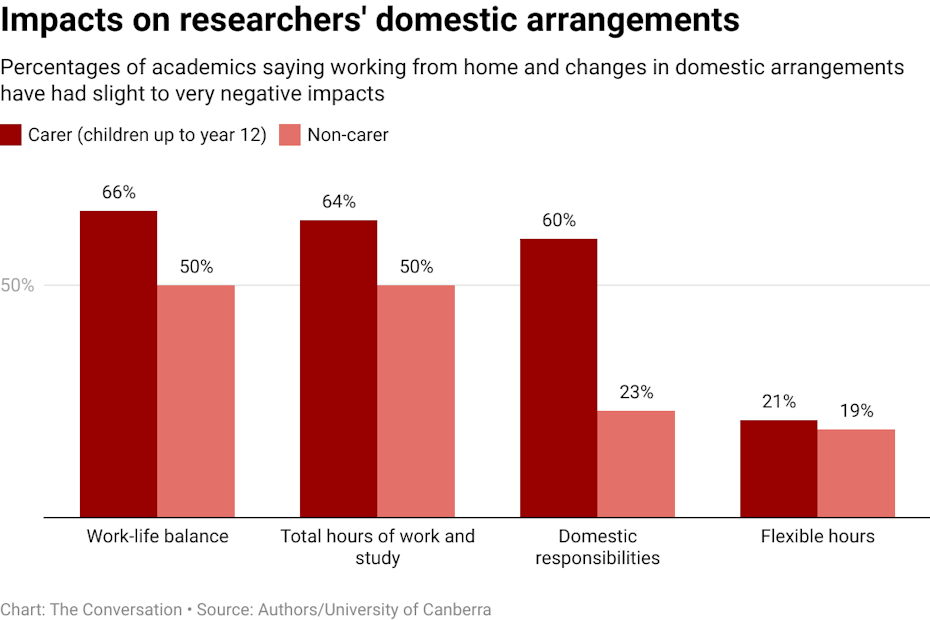

However, working from home did not translate into work-life balance and productivity for many academics. Domestic arrangements for a significant number have had an overall negative impact. These impacts particularly affected those with carers’ responsibilities.

Of those with children up to year 12, 64% said working at home had a negative impact on the hours of work, compared with 50% of those with no children at home. Those with children at home were three times more likely to say their domestic responsibilities had a negative impact on their research.

The impacts of COVID-19 on academic staff are not evenly distributed. There was a disproportionate gender impact, which is in line with previous reports across the sector. Impacts were greatest on academics in the early stages of their careers, often with young families.

This differential impact is reflected in other research into academic publishing, which shows the gender gap widening during the pandemic.

What does the future hold?

Research is a long-term endeavour. It takes years and even decades for research to come to fruition.

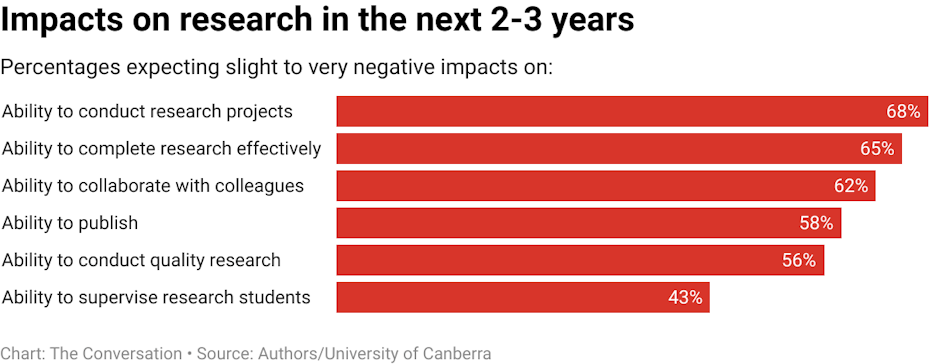

We asked respondents how they saw the future of their research. The majority felt pessimistic about all aspects of research: funding, publication, collaborating and supervising PhD students. More than two-thirds of respondents had negative views about their ability to attract funding and pursue research projects in the near future.

More importantly, those who have young families are feeling despondent about their research careers. A majority of them say their ability to publish will be hampered for the next two to three years. This group is the future of Australian academic research, so the negative impact of COVID-19 is of serious concern.

This is bad for Australia in terms of lost or delayed advances in science and technology, stalled or postponed advances in health care and treatment, reduced capacity to inform public debate, and fewer opportunities to contribute to Australia’s lifestyle and culture. The impacts of the pandemic on the emerging generation of researchers will have long-term consequences.

In June, the ABS survey of pandemic impacts found one in five (20%) Australians experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress due to COVID-19. This has not changed since last November. Like many Australians, academics are under enormous pressure trying to balance work and home life.

As well as the concerns about the blurring of work and home life, we found evidence of low morale and exhaustion among staff. These findings match those of a report released today by Professional Scientists Australia.

There is a need for both the government and universities to develop a long-term, tailored strategy to support the research community. This will help ensure Australia’s research effort continues at its above-world-class level, with the associated societal benefits it brings.

The survey and the analysis of the data were carried out in collaboration with Janie Busby Grant, Elke Stracke, Simon Niemeyer, Roland Goecke, and Dianne Gleeson at the University of Canberra.![]()

Sora Park, Associate Dean of Research, Faculty of Arts & Design, University of Canberra; Jennie Scarvell, Associate Dean of Research and Innovation, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, and Linda Botterill, Associate Dean Research – Strategy & Performance, Faculty of Business, Government & Law, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.