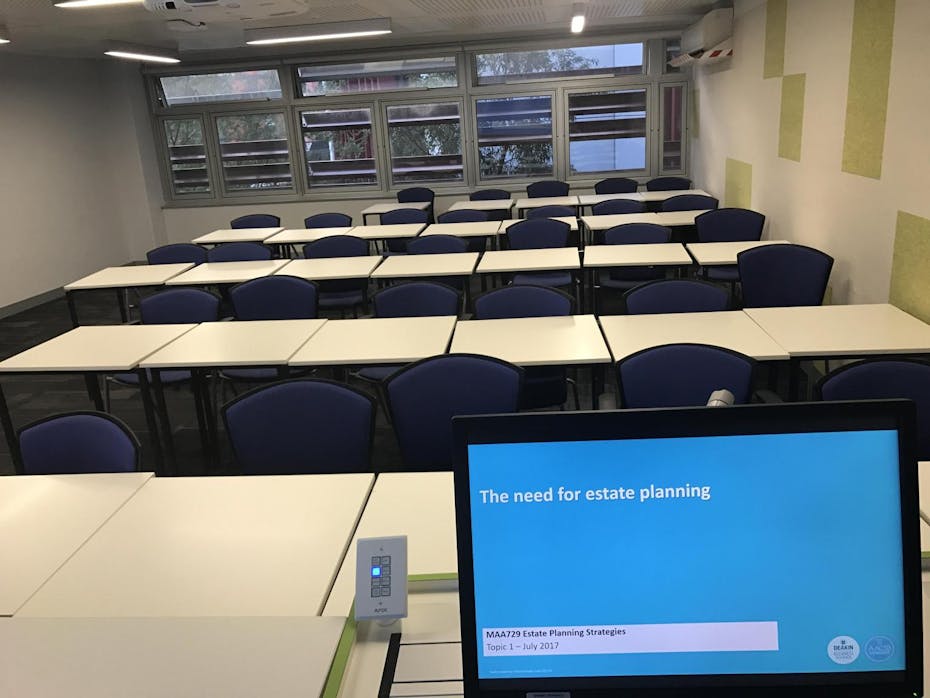

In 2017, a business lecturer posted a photo on LinkedIn showing a completely empty university classroom, 15 minutes after the class had been scheduled to start.

This is not an isolated incident. Anecdotally, lecture and tutorial attendance has been declining steadily in Australian universities and faculties for many years.

Declining attendance may affect students’ academic performance and their sense of connectedness. University doesn’t only teach content but develops attributes such as oral communication and interpersonal skills including teamwork.

Students are less likely to develop these skills if they don’t physically attend class.

We conducted a large-scale study in our law school to uncover whether lecture recordings are responsible for declining student attendance and what motivates students to attend or miss class.

By manually counting how many students were in lectures across sixteen different subjects, we found attendance rates averaged just 38% of total enrolments across the semester.

Adrian Raftery/LinkedIn

There was a natural ebb and flow of lecture attendance throughout the semester. There was peak attendance at the beginning (57%), a significant drop in the middle as assessments became due (26%) and a rebound at the end of semester as exam season hit (35%).

We also asked students to self-report their lecture attendance. The most common answer given, by far, was “almost all of the time” and 59% of students said they attended lectures the majority of the time.

Clearly there is a dissonance between this self-perception and reality.

Are recordings to blame?

Lecture recording is now common in Australian universities. Anecdotally, it’s often held responsible for declining attendance rates. But there is little research on the relationship between student attendance and lecture recording.

While lectures are usually recorded and available to students in streamed or downloadable format once the class ends, tutorials and other smaller classes are not usually recorded.

Our study found students aren’t ditching tutorials, seminars and workshops as much as they are lectures. Tutorials averaged a whopping 84% attendance rate. This could partly be explained by the fact teachers assess students on their participation in tutorials.

We also surveyed 900 students to find out their reasons for attending and not attending lectures, tutorials and workshops.

Availability of lecture recordings was the most common reason students gave for not attending lectures (18% of students said this). But work commitments were a close second (16%). Then it was timetable conflicts (12%), the time and day of lectures (11%) and assessments being due (8%).

Students lead complex lives

Universities provide students with lecture recordings for several reasons. These include giving students an alternative study tool and supporting students with disabilities or from non-English speaking backgrounds (who can slow down or pause recordings if necessary).

Our survey and focus groups showed students lead complex lives often balancing work, family and other commitments alongside their studies.

One student said:

[…] if some [lectures] are so early as 8am, that would involve waking up at 6am, which is difficult as I work in hospitality at night and if I’ve worked the night before I wouldn’t be getting to bed until after midnight.I likely would be fatigued during that lecture and have difficulty concentrating and taking in the content, compared to if I watched the recording and took notes later that afternoon.

Other students said they relied on lecture recordings to enhance their learning. One said:

I find I get more out of the lecture by listening to it in my own time and at my own pace […] I prefer to be able to pause the recorded video to research more in-depth into cases and theories to add to my notes.

Some students with additional learning needs said the option not to attend class, and to access lecture recordings, was an important equity measure.

What should we do?

Lecture recordings bring important benefits for students. They can also be necessary for students with personal, work or health difficulties.

But recordings are clearly contributing to declining lecture attendance, too. We propose three possible paths forward for universities and teachers, each with their own advantages and disadvantages.

First, we can simply persist with the traditional model of recorded lectures. Teachers will need to accept attendance will likely be low and student learning, experience and wellness should instead be the focus of tutorials and other small group classes.

Second, we can introduce more active learning into lectures to encourage greater attendance. This could include small group exercises, in-class polling or role-plays.

But this would mean lecture recordings would be less useful for students. It would undercut the flexibility recordings offer and may cause equity concerns.

Third, we can change our teaching methodology to a “flipped” approach. This means the main way students would get information would be through online resources and activities. Face-to-face classes would then be dedicated to engaging students in deeper learning through collaborative activities.

Though this frees up lecture time for more effective learning, it would require appropriate support and training for teachers. Teachers, many of whom already work under significant time constraints, would need to invest more time and energy into their lessons.

Unfortunately there is not a one-size fits all answer to the conundrum of declining lecture attendance. But learning and teaching policies, such as mandatory lecture recording, should be informed by an evidence-based understanding of the likely consequences for staff and students.![]()

Natalie Skead, Professor, Dean of Law School, University of Western Australia; Fiona McGaughey, Senior Lecturer, Law School, University of Western Australia; Kate Offer, Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Western Australia; Liam Elphick, Adjunct Research Fellow, Law School, University of Western Australia, and Murray Wesson, Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.