THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nathan Denette

This week, Ontario teachers have planned provincewide rotating strikes. The Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario says this is the first time in more than 20 years that four education unions have moved into a strike position.

This news comes after months of discontent among teachers’ unions and a December job action by the union representing Ontario secondary school teachers.

For some residents, this disruption in education under Doug Ford’s Conservative government may come as a surprise.

CP PHOTO/Fred Chartrand

However, to those who have followed developments in how the province has managed education over the past two decades, it is in many ways a chilling reminder of the school fallout of 1995-2002, when Mike Harris was premier.

In 1997, an Ontario-wide teacher strike affecting more than two million students was at the time the largest teacher strike in North American history, according to media reports.

Manufactured crisis

Harris’s Progressive Conservative government shaped educational policy through his vision of a “Common Sense Revolution.” The Ontario premier believed that schools, school districts and teaching staff were ineffective and inefficient. His “revolution” sought to bring a degree of restraint to a system that he deemed was out of control and in chaos.

In September 1995, Harris’s education minister, John Snobelen, was caught on tape announcing his government’s mandate to create a crisis in education in order to gain public support for reform. The tape became public and efforts to control the damage began.

One of the major ways that governments respond to such issues are to reinforce measures of control. As Oscar Wilde, the Irish poet and playwright said, “Nothing succeeds like excess.” Snobelen later admitted he had made the case for greater accountability in education sound more critical than it actually was.

Neoliberal education

While Harris introduced a comprehensive program that aimed to reduce taxes while balancing the budget and reducing the size and role of government, his plan closely mirrored the politics of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and U.S. President Ronald Reagan. These governments drew on 19th-century neoliberal ideas associated with laissez-faire economics and free market capitalism.

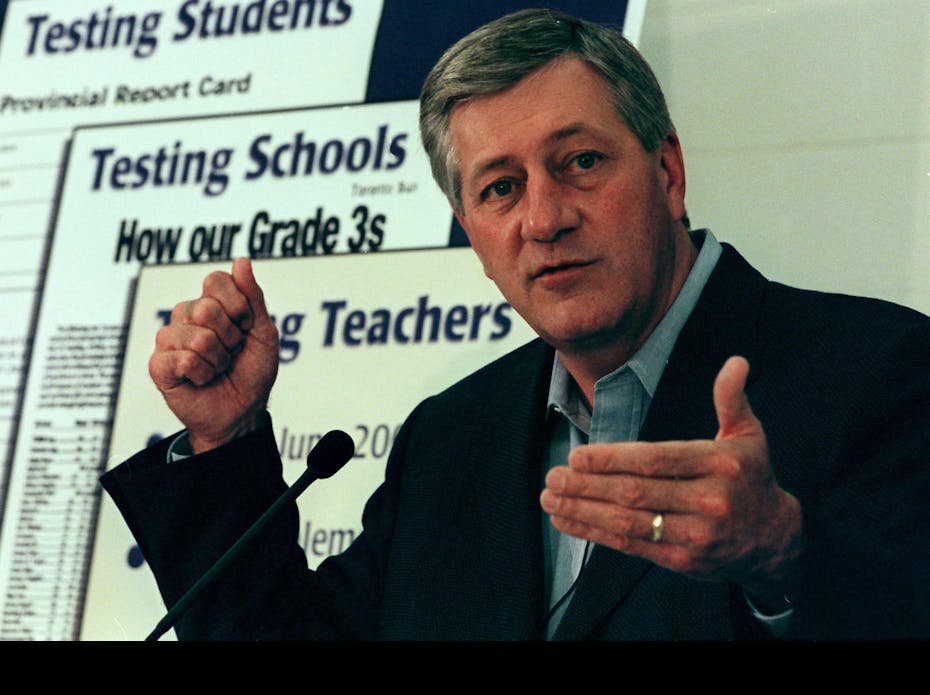

(CP PHOTO/Frank Gunn)

Creating a crisis in education by calling into question teacher professionalism has become a familiar strategy by neoliberal educational policy-makers.

Journalist Naomi Klein has argued that advocates of neoliberal free market policies have sought to exploit or even create crises in order to push controversial policies on citizens while they are too distracted to mount resistance.

The neoliberal model for analyzing education examines students primarily as human capital who must become more economically competitive as future workers, and must develop the skills and attitudes to compete efficiently and effectively.

Math scores first attacked

In Harris’s Ontario, student math scores were attacked, followed by literacy scores. However, these attacks soon became a general call for greater accountability overall, including the periodic testing and re-certification of teachers.

Harris’s government called for standardized testing and the Education and Quality Accountability Office Act (EQAO) was passed into law in 1996.

Currently, the EQAO oversees reading, writing and mathematics testing for grades 3, 6, 9 and 10. Although the process may have been somewhat clandestine, the message was obvious. The attack on education to justify outcomes quantified as scores had begun.

Outcomes-based education

Standards-based education fits in current contexts of neoliberalism, in which schools are often viewed as consuming huge amounts of money without producing adequate results.

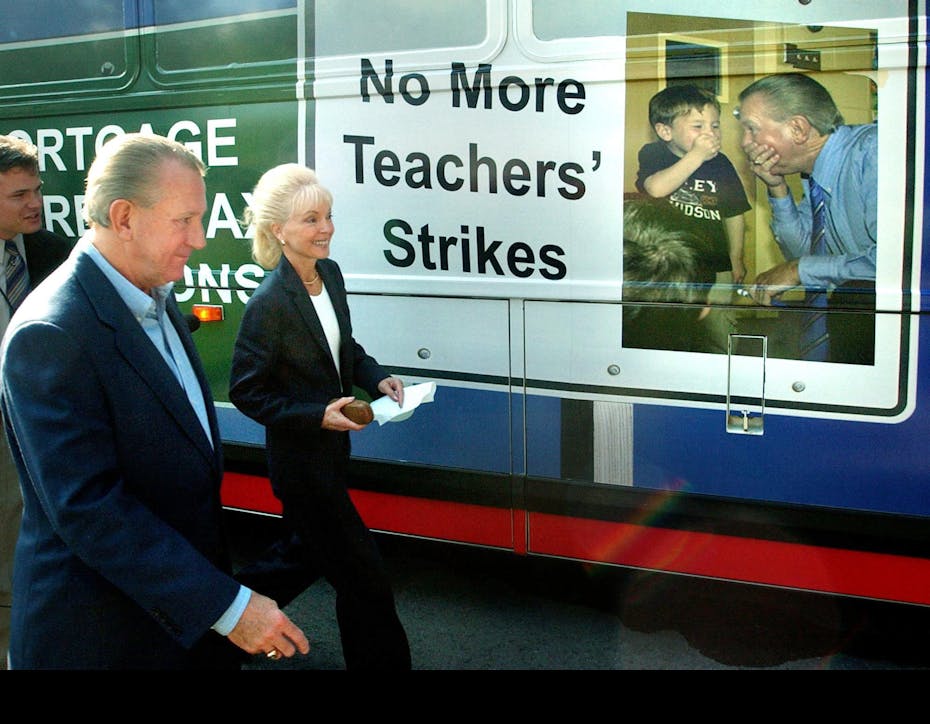

CP PHOTO/ Rene Johnston

But isn’t it more costly to society — and to the economy — if cuts erode opportunities to positively shape young people’s lifelong success through early and ongoing quality education?

Neoliberal educational reform had its beginnings in the United Kingdom, and the Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED) continues to monitor the success or failure of public schools to improve student achievement scores in Great Britain. The United States and other countries have followed suit with outcomes-based education wedded to standardized testing.

Compulsive standards?

Education researcher Linda McNeil of Rice University notes in her book Contradictions of School Reform that high student scores doesn’t necessarily mean students are learning for the long-term.

CP PHOTO/J.P. Moczulski

Students become adept at test-taking, she argues, but do not retain what they’ve learned because it never moves to the long-term memory. Tests typically rely only on short-term memory, which is why progressive education tends to be more projects-based than exam-based.

Her analysis also points to the compulsive nature of standardizing education whereby teachers are forced to take time away from teaching the curriculum to prepare students for tests. This is becoming a global phenomenon in the name of a vibrant economy.

As standards-based education has grown and teachers’ credibility or professionalism is besmirched, private corporations have benefited.

Multi-trust academies have benefited financially by taking over failing schools in the U.K. Companies that offer education modules, tutoring or lesson plans reap benefits as fee-for-service providers. Indirectly, they may also benefit if teachers, strapped for time and resources, rely on free corporate lesson plans, such as through Disney lesson plans. While the impacts are global, the implications are local.

In Ontario, educators’ rotating strikes are drawing attention to the needs of their students. Will the solution be to offer more standardized tests and more competition? Only time will tell.

In the meantime, Yogi Berra, the famous baseball player, may have said it best: “It’s like déjà vu, all over again.” We have been here before.

![]()

Stephanie Chitpin, Professor of leadership, Faculty of Education, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.