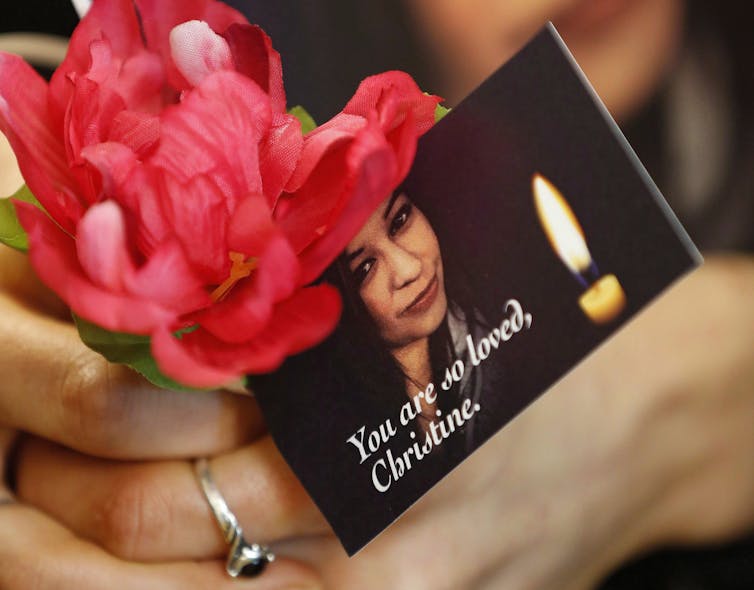

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

As an American Indian woman who recently moved to Canada, I’ve been saddened to see that the systemic and insidious racism towards Indigenous women and girls that is happening in the United States is also happening in Canada. My new provincial home, British Columbia, has the highest proportion of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls.

I am still processing the final report on the National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) that was released this week. The report is over 1,200 pages and includes more than 230 recommendations.

But what I can say is that compared to the lack of moral outrage in the U.S. on this issue, I am hopeful by the very fact that in Canada, after much activism, such a committee was formed and a report of the findings were released with a bold statement. The inquiry concluded that the murder and disappearance of Indigenous women and girls is an ongoing genocide.

Maybe this will shake people out of complacency.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

I am hoping to learn more next week when the chief commissioner on the National Inquiry, Marion Buller —a member of the Mistawasis First Nation in Saskatchewan — delivers the keynote at a conference I helped to organize. The conference, in partnership with Georgetown University at the University of British Columbia where I am on the Faculty of Nursing and head up the First Nations House of Learning, brings together people from both sides of the Medicine Line (U.S./Canada border). Those people include newly elected North Dakota state Rep. Ruth Anna Buffalo and Annita Lucchesi, who maintains an extensive North American database of MMIWG cases.

A lack of moral outrage

The murder and disappearance of Indigenous women and girls are occurring at stunning rates at both sides of the Medicine Line, with shared historical reasons.

In the U.S., there are far higher levels of violence towards American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) women than the general population. In many reservations and counties, AI/AN women face murder rates more than 10 times the national average. According to a February 2017 report from the National Congress of American Indians, one in three AI/AN women are raped in their lifetime; 86 per cent of perpetrators are usually Non-Indian.

Perpetrators are rarely caught, prosecuted or stopped. And this information or epidemic is seldom reported in the news.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/John Woods

The root causes, though broadly similar to those found in Canada, are also embedded in U.S. law. The U.S. has laws as old as 1880 that allow non-Indigenous perpetrators on Indigenous territory to essentially go free.

Some have described this as “open season” on AI/AN women. “Open season” refers to the relative ease of non-Indian perpetrators to enter Indian lands to assault and rape AI/AN women, often resulting in their murder or going missing at disturbing rates and without consequence.

Another reason is inadequate policing resources. My tribe, for example, the Three Affiliated Tribes of North Dakota, has a million-acre reservation, which is equivalent to a small state. The tribal police force there is stretched beyond reason, with only two dozen police officers covering this large area. This situation is not uncommon at other U.S. reservations.

State representatives address the epidemic

Unlike in Canada, in the U.S., there is no national inquiry. Very little has been done to address these shocking and sad realities at the federal level. Last year, Savanna’s Act proposed that the Department of Justice (DOJ) update federal databases relevant to cases of missing and murdered Indians to include the victims’ tribal enrolment information or affiliation. The act also aimed to create protocols and training for law enforcement and others as well as consultation with tribes.

For a variety of reasons, the bill did not pass through both chambers and was stuck.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jason Franson

But there is some hope. U.S. state legislators, especially those with reservations, have stepped forward. Representative Buffalo has already introduced two bills on missing and murdered Indigenous people. Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, South Dakota and Washington have also passed legislation to address the MMIWG crisis.

The proposed legislation introduces the most basic concepts of collecting accurate and timely data, sharing that data with the FBI and other databases, and establishing targeted training for law enforcement and others on the MMIWG epidemic.

While these developments are laudable, these states only represent six of 34 states that together hold 573 federally recognized Tribal Nations. As to U.S. Congress and other federal leaders, they need to take a look at Canada. There needs to be a national response.

Canada’s final report

The final report of Canada’s MMIWG inquiry calls on educators and post-secondary institutions to educate the public about missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and about the root causes of violence they experience. Such education must include historical and current truths about the genocide against Indigenous peoples through state laws, policies and colonial practices.

It should include, but not be limited to, teaching Indigenous history, law, and practices from Indigenous perspectives and the use of Their Voices Will Guide Us with children and youth.

As an American Indian Woman who holds lineage and has lived on both sides of the Medicine Line, it is my fervent hope that both countries will soon fully engage themselves in learning about this horrific and yet preventable scourge of violence toward my sisters in spirit — equally followed by whatever decisive action is necessary to stamp it out.![]()

Margaret Moss, Associate Professor and Director of the First Nations House of Learning, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.