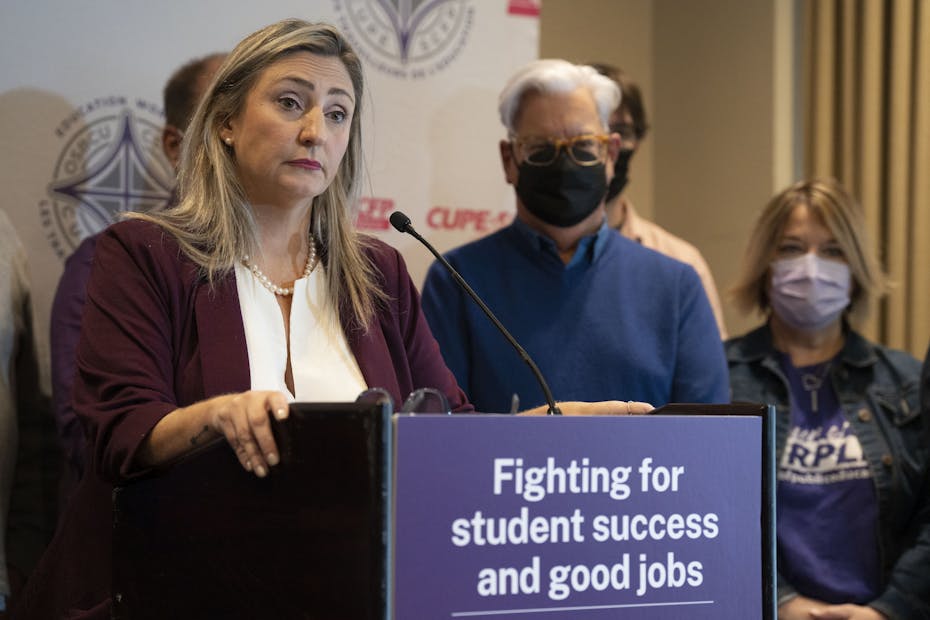

THE CANADIAN PRESS/John Woods

Labour issues in education across Canada have made the headlines in recent weeks.

Think of the over 50,000 education workers in Ontario represented by the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE).

They walked off the job on Nov. 4 in protest over Premier Doug Ford’s anti-strike legislation and another strike was narrowly averted Nov. 20.

Or think of 600 educational workers in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley area, including those from a school district covering 40 schools and two adult high schools, who walked out on Oct. 24th over wage parity concerns.

Educators at Dalhousie University who are part of Nova Scotia’s largest university union, CUPE 3912, representing teaching assistants, sessional instructors and markers, withdrew their labour on Oct. 19, after multiple rounds of negotiations failed.

The strike ended Nov. 12. The agreement includes a 23 per cent raise for part-time academics and teaching assistants, and a 44.5 per cent raise for demonstrators and markers by September 2023. While workers are pleased to be back in classrooms, these increases fall far short of pay parity with research-intensive universities.

What these fights have in common is that they emerged in education. Yet these are also political fights, part of a broader movement for workers’ rights and better occupational conditions.

University labour unrest across the country

These strikes are happening in a time when corporate profits have skyrocketed.

Political fights are about members’ control over working conditions — not only salaries and wage classifications but also factors like safety rules and staffing levels.

University strikes in face of austere working conditions that keep instructors in situations of precarious labour have been bubbling across the country.

Instructors at University of Toronto voted in favour of a strike on Nov. 4. The Cape Breton University Faculty Association (CBUFA) voted in favour of strike action in September this year. So did the Western University faculty union in early October.

Contract instructors at the University of Toronto are asking for good jobs and good pay so in the future strikes can be avoided. For CBUFA members the conciliation process begins Dec. 13, and will address salaries and human resource needs. At Western University, an 11th hour agreement averted a strike focused on equitable workloads, equal access to benefits and job security for contract faculty members.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Chris Young

Class struggle

University strikes represent symbolic cross swords between the “haves” and the “have-nots” in society — an ongoing battle between highly paid administrators and low-waged workers.

Often lacking stable employment options, teaching assistants and sessional instructors find themselves accepting multiple contracts to meet their basic needs and those of their families.

At Dalhousie University, teaching assistants and markers, with hourly rates of $16.61-$24.41, were paid below or near the living wage in Halifax.

University of Toronto pays $47 per hour and Western University pays $46.

Halifax faces an acute housing crisis and rising costs of living. In 2022 alone rent costs increased by 9.3 per cent and food costs by 8.8 per cent.

Wages for sessional and teaching assistant staff at Dalhousie University had remained stagnant. However, salaries for administrators and senior staff increased from eight to 13 per cent.

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is a form of aggressive capitalism. It wages war on the welfare state, the provision of public good and the social contract. The idea of a social contract implies we all have a responsibility to care for each other. It highlights that government and institutions have a collective responsibility to provide a living income, adequate and affordable housing and to create policies designed to promote social equity and well-being.

This is particularly relevant as we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Neoliberalism has been the guiding political philosophy in Canada and the global economy since the 1980s. It facilitates the privatization of goods and services and a regime of corporate rule which impacts all aspects of our society, including our educational institutions.

Unions fighting for a liveable wage and work improvements are small fry when one considers the multimillion dollar financial budgets managed by public Canadian universities. Their fight symbolizes more than wage increases as it opposes the values of neoliberal rule.

The corporate university

Education, philosophically speaking, has traditionally been envisioned as a public good rather than as a commodity. The difference between goods and commodities being that a good does not have monetary value. It has experiential value.

Universities are assigning monetary value to a good envisioned as experiential in nature.

Under this model, students replace their role as learners to customers expecting service. Faculty become responsible for delivering and guaranteeing a pleasant service experience.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn

Degrading academic standards

This is exactly why university administrators have sometimes suggested academic continuity is necessary to reduce the impact from the loss of labour when workers strike. The idea of academic continuity is imported from theories of business continuity management.

The principles of academic continuity were tested at the University of Toronto when teaching assistants went on strike in 2015. Faculty and librarians wishing to demonstrate labour solidarity were told not to withdraw their own labour and to oversee the “smooth management” of courses. Decisions to continue to teach courses to mitigate the negative impact of the strike on students put faculty in a difficult moral position, causing them moral distress.

Proposed under the guise of student benefit, such measures have an anti-strike purpose and can degrade academic standards.

Critical thinking needed

As far-right governments gain popularity globally, the need for critical thinking, a hallmark of university education, is an antidote. Critical thought is needed to safeguard academic freedom, democracy and values that recognize the inherent worth and dignity of human beings.

Labour strikes are everyone’s fight. Resistance to neoliberalism and the corporatization of education matters to our collective future and it prioritizes equity, social justice and concern for those most marginalized.

Educational institutions are microcosms of society at large. They teach students to navigate and address our urgent societal challenges and train future generations of political leaders. Leaders need to know that workers’ rights are matters of public good and not matters to be trumped in the name of corporate regulation.![]()

Nancy Marie Ross, Assistant Professor, Social Work, Dalhousie University; Raluca Bejan, Assistant Professor, Social Work, Dalhousie University, and Steph Zubriski, PhD Candidate, Health, Dalhousie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.