Over the past month, industrial action by academics has seen picket lines outide many universities in the UK. Supported by members of the student body and a range of other education workers, academics have stood outside in the cold, encouraging their colleagues to not enter the buildings, and to instead join the strike outside.

These strikes are part of a long and inspiring history of denying access to physical space as a form of protest. From the eponymous character in Aristophanes’ comedy Lysistrata seizing control of the Athenian state treasury in the 5th century BC, to the wall of 30,000 women surrounding Greenham Common air base in England in 1982, or the pickets of the 1984/85 UK miners strikes, blocking entrance to the workplace is one of the oldest methods of allowing the many to fight the few.

The aim of the blockade in each of these cases was to separate the worker from the means of their production, forming a physical barrier preventing employees from reaching, in those cases – war funds in the Acropolis, weapons of war at the air base, or machinery in the mines. Blocking access to space made sense because blocking access to space meant blocking access to work. But the difference between these historical strikes and the ongoing university action is that work, and the way we access it, has fundamentally changed. Work, for so many, is no longer a place that you go, but a thing that you do.

Most academics, most UK workers, and an increasing percentage of humanity, wake up not to go to work, but to find work lying next to them on laptops, tablet computers or smartphones. Work now sits next to you on the bus or the train, it joins you at the dinner table, it flies with you on holiday. For most workers, particularly in cities, the product of their labour no longer requires machines tied to buildings, with those employed in service industries now outnumbering those in manufacturing by a factor of 10. Instead they produce knowledge, as the working class has become the clerking class.

This poses new questions to those attempting to withdraw their labour in 2018. During recent strike days in the UK, while academics were refusing to work physically within their institution, many continued to publish work through blogs and social media, videos of lectures remained available on YouTube and online courses, and many staff and students were encouraged to relocate activities off-site, in cafes, pubs or halls of residence. These activities included not only strike-based “teach outs” but also research meetings and reading groups not considered to be the “core work” of academia.

Our conception of the “picket line” has not caught up with the fact that digital technologies have reframed how and where we can carry out work. In practice, this means an employee can produce work at home on their laptop conscience clear that they have not broken the physical picket line. To quote a research student who took part in the recent UCU strike: “We are striking, but we have not stopped working.” And to quote a professor who was regularly on the picket line: “I doubt any staff member will actually stop working altogether, we are on strike, but we are not striking from doing work.”

So here there’s an issue – the widespread use of mobile technologies means that a picket line is no longer encouraging people to strike from work, but to strike from space.

Nonetheless, some genuinely disruptive methods of “digital protest” have emerged. Early this year, unionised workers of the news organisation Vox all signed out of Slack, the company’s internal messaging system, disrupting productivity en masse, even if only for an hour. And on November 10 last year, as part of Equal Pay Day, female employees of companies across the world switched on the “out of office” on their emails, leaving every customer, client and colleague with a note that due to discrimination they were really not being paid for the rest of the year.

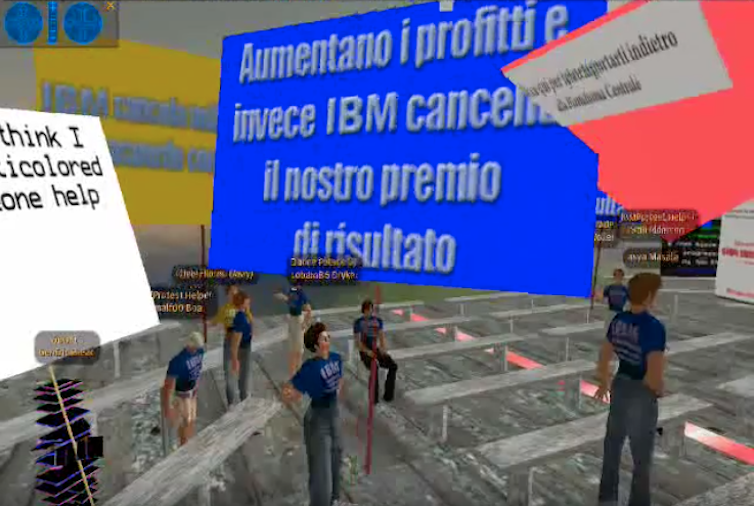

The most novel use of the digital to protest has to go to Italian employees of the tech firm IBM back in 2007. Prior to the strike, IBM had decided to invest a significant sum on a headquarters in the virtual world Second Life, to be used not only as an advertisement for the company, but to actually host internal company meetings between executives stationed across the world. When the strike occurred, then, workers protested in both physical and digital space, with 1,850 protesting avatars storming the company’s virtual business centre. Teleporting in and out of virtual meetings, taking the form of geometric shapes, placards with legs, and a range of angry fruit, the workers succeeded in disrupting their bosses who were on the other side of the physical world.

RSUIBM / Youtube

Before we answer the question of how workers withdraw labour in the digital age, though, we first need to work out what actually counts as labour. Unlike workers in France or South Korea, those in the UK have no right to be disconnected. The line between work and leisure is becoming increasingly blurred, with British academics regularly working 50 or 60 hour weeks, and contributing an estimated £3.2 billion of pro bono work each year. By being on the picket line only during teaching hours, while carrying on answering emails or publishing blogs, academics risk discounting these activities as outside their “proper work”.

![]() During the current dispute, many university staff have had to answer questions about what really counts as work to strike from. What if you are on sabbatical? What if you are in the field, or attending a conference in another country? And the wider problem for everyone whose work is based around producing knowledge, is that it is almost impossible to strike from thinking. This applies to me, too. As an anthropologist who researches work in the digital age, by thinking about the protests while on the picket lines, in order to eventually write about it – did I break the strike?

During the current dispute, many university staff have had to answer questions about what really counts as work to strike from. What if you are on sabbatical? What if you are in the field, or attending a conference in another country? And the wider problem for everyone whose work is based around producing knowledge, is that it is almost impossible to strike from thinking. This applies to me, too. As an anthropologist who researches work in the digital age, by thinking about the protests while on the picket lines, in order to eventually write about it – did I break the strike?

Joseph Michael Cook, PhD Researcher, Material Culture Anthropology, UCL

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.