Convocation can be a very emotional occasion. Each year, it seems, the commentariat is whipped up into near hysterics over some honorary degree recipient or guest speaker. This year’s panic came by way of the University of Alberta’s acknowledgement of David Suzuki.

Much less attention is devoted to who is not at convocation. In fact a moral indignity continues to unfold without much notice. Each year — and without fail — very few Indigenous people find a place among the graduands.

Recently released data from the 2016 Census confirms that post-secondary convocation is a festivity reserved more for the settler population than it is for the Indigenous.

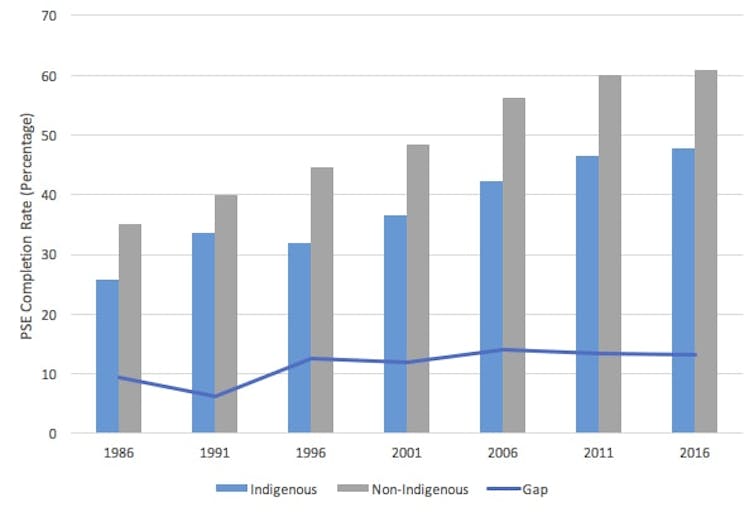

According to this data, there is a noticeable Indigenous-settler post-secondary education gap of more than 13 percentage points for those aged 25 years and over. In this age range, approximately 61 per cent of non-Indigenous individuals hold a post-secondary credential, whereas only 48 per cent of Indigenous people can make the same claim.

As convocation ceremonies roll out across the country with few Indigenous folks in the class of 2018, we should not be surprised. The outcome reflected in the 2016 census data was contrived long ago.

The post-secondary birthright lottery

The pageantry around being admitted to a degree, to receiving a diploma or certificate, has always been exclusive, restricted largely through the settler birthright lottery. But the Indigenous-settler post-secondary education (PSE) gap wasn’t supposed to be around today.

In fact, the 2016 census was supposed to bring some long-awaited news for Indigenous peoples: Equality in PSE outcomes.

Back in October of 1996, the final report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) addressed the PSE gap.

RCAP constructed a funding proposal which concluded that “20 years should be sufficient to achieve parity in participation and performance in post-secondary education.”

When implemented, RCAP’s proposal would bring hope to Indigenous youth of the mid-1990s as they came of age at a time when target programming and policy would close the PSE gap.

But RCAP was not implemented. And, somewhat perversely after all the effort invested by Indigenous peoples into the commission, the Liberal government of the day actually cut funding to support Indigenous people.

The 1997 Canadian budget, delivered by former Prime Minister and then-Finance Minister Paul Martin, announced that, “The rate of growth in transfers under the Indian and Inuit programs (Department of Indian and Northern Affairs and the Aboriginal health programs administrated by Health Canada) is being restrained.”

Producing an underclass

These policy moves charted the destiny of many Indigenous people who are in the early years of adulthood today.

While they were infants and toddlers, Ottawa ensured that the educational trajectory of Indigenous youth of the 1990s — a cohort that was meant to feed much of the graduating class of 2018 — would follow the familiar colonial pattern of malignant neglect.

“Restrained” programs across the entire spectrum of life, programs that were already grossly inadequate, ensured that most Indigenous children of the 1990s would not be able to access higher education in the 2010s.

The policies of the 1990s ensured that the prospects for improved Indigenous PSE outcomes would be dismal in 2018.

(Veldon Coburn), Author provided

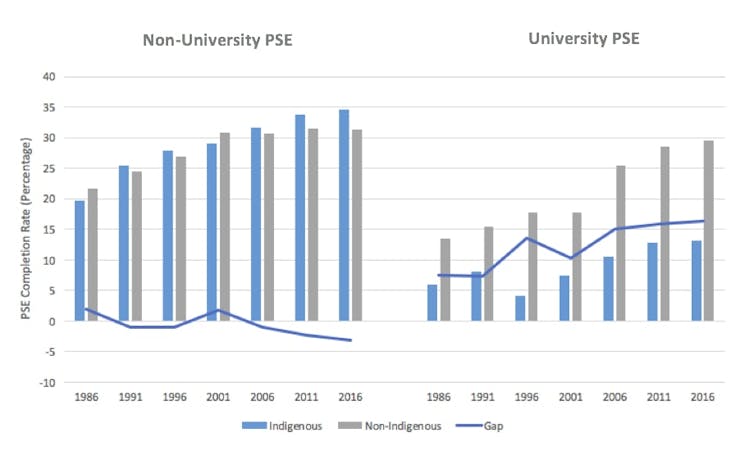

What’s more, the restrained investment in Indigenous education suggests a noticeable substitution effect at work. With comparatively less support for education at all levels, Indigenous people are choosing cheaper PSE programs as substitutes for more costly alternatives.

We see that the Indigenous-Settler PSE gap is, in fact, due entirely to Indigenous students choosing less expensive, non-university education — trades, apprenticeships, CEGEP and community colleges — over the comparatively expensive university programming.

(Veldon Coburn), Author provided

In effect, federal Indigenous education policy has produced an underclass of the Indigenous population.

Restrained, insufficient investment is disproportionately pooling Indigenous students into education that will lead to a working class career. It is directing them away from professional class opportunities that come with university degrees in business, law, health, engineering and so forth.

‘Shannen’s Dream’

Very little has changed between then and now. Federal Indigenous policy and programming is reproducing inequalities recognizable a generation ago.

In 2004, an analysis by the Auditor General noted that it would take 28 years to close the high school completion rate between on-reserve First Nations and the rest of Canada.

Wilful and knowing under-funding of all Indigenous public programming, especially education, continues to sustain the PSE gap.

In late 2016, the Parliamentary Budget Officer reported that federal spending on elementary and secondary education for First Nations on-reserve falls considerably lower than what the provinces would spend according to provincial formulae.

Despite this, Indigenous people continue to hold onto hope. Before tragically passing away in June 2010 at age 15, Shannen Koostachin advocated determinedly for improved educational outcomes for Indigenous people.

A Cree student from the community of Attawapiskat — a First Nation signatory to Treaty 9 which stipulates that “His Majesty agrees to pay such salaries of teachers to instruct the children of said Indians, and also to provide such school buildings and educational equipment as may seem advisable to His Majesty’s government of Canada” — Shannen dreamed of a proper education for Indigenous people in safe schools.

A government responsibility

Shannen’s Dream was a precursor to the educational Calls to Action issued by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Her dream for safe schools — rather than the mould-infested, run-down facilities she attended for her elementary schools — is part of a larger vision of properly supported Indigenous education, to close the gap between Indigenous-settler educational opportunity and achievement.

This government is well aware of its role and responsibility to remedy these unacceptable conditions and poor educational outcomes. Not long ago when she was in opposition in the House of Commons, the current Minister for Crown-Indigenous Relations, Carolyn Bennett, acknowledged as much.

Back in May 2015, Bennett had sharp words for then-Minister of Indigenous Affairs, Bernard Valcourt: “I would suggest the minister go and sit in the offices of those First Nations as they pore over the backlogs and the wait lists. The fact is it is the responsibility of the Government of Canada to get these students who have been accepted into post-secondary education that much needed education.”

![]() Perhaps Minister Bennett could heed her own words.

Perhaps Minister Bennett could heed her own words.

Veldon Coburn, PhD candidate at Queen’s University’s, Anishinaabe from Pikwàkanagàn, Lecturer, McGill University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.